Marsh Wren

General Description

The Marsh Wren is usually not seen for long, as it pops up from dense emergent vegetation, only to duck back out of sight moments later. Small and stocky, with the classic wren tail held upright, the Marsh Wren is easily identified as a wren. The upperparts are brown with a black patch streaked with white, and the tail is barred with black. In Washington populations, the shoulders are brown, unmottled, and much duller colored than those of Marsh Wrens in eastern North America. The belly is gray-brown, lighter than above. The throat is light, and the white eye-line and brown crown are field marks to note.

Habitat

Emergent vegetation is the most significant component of nesting habitat for Marsh Wrens. They inhabit freshwater and saltwater marshes, roadside ditches, and small agricultural runoff sites, and will even nest in invasive plants such as purple loosestrife and reed-canary grass. In winter, they frequent a wider variety of habitats, including wet meadows and coastal dune grass. In eastern Washington, early nests are typically built in cattails, but after mid-June, over 90% of the nests built are in bulrush. (Bulrush grows in deeper water than cattails, and is more likely to be under water after the marsh has dried up around the shallower cattails.) In western Washington, Marsh Wrens inhabit wetlands with both cattail and bulrush, and have also been known to nest in emergent hardhack.

Behavior

Marsh Wrens glean food from the stems of dense marsh vegetation, from the ground, or on the water's surface. They usually forage out of view, hopping up for brief moments when they can be seen by patient observers. Like other wrens, male and female Marsh Wrens of all ages will destroy the eggs of their own and other species. Washington's Marsh Wrens build between 14 and 22 incomplete 'dummy' nests, which may help with predator avoidance. The dummy nests are also used throughout the year for shelter, and dummy nests of resident birds tend to be sturdier than dummy nests of migrants who do not use them for winter shelter. In fact, western Washington Marsh Wrens, which use their dummy nests for shelter in the winter, spend significantly more time building them than their eastern Washington counterparts who migrate and don't need the winter roosts. Male Marsh Wrens have up to 200 songs, which they sing almost continuously during the breeding season. Their songs resemble the sound of a sewing machine.

Diet

Like most wrens, Marsh Wrens eat primarily insects and spiders. They eat aquatic insects as well.

Nesting

Marsh Wrens are polygamous, with about half of the males in Washington having two or more females on their territory at one time. The male builds many unfinished nests and then shows them to the female, who selects one and adds a lining to it. This process starts in March in western Washington and in early April in eastern Washington. The nest is anchored to standing vegetation, 1-3 feet off the ground, and is an oval mass of grasses, cattails, and sedges woven together with an entrance at the side. The lining is made of fine grass, plant down, and feathers. The female incubates 4 to 5 eggs for 13 to 16 days, and broods the young for about a week after they hatch. In western Washington, males help feed the young, but in eastern Washington, males don't help feed the early-season clutches. Later in the season, when there is less chance of attracting new mates, they will help feed. The young leave the nest after about 13 to 15 days. In western Washington, the parents continue to feed the young for another week or two. Once the young have fully fledged, the female will raise a second brood.

Migration Status

Migration is variable throughout the range. Wintering grounds for migrating birds can be found throughout the southwestern United States, in pockets of the southeast United States, and in Mexico. Eastern Washington populations are migratory, while west-side birds are resident.

Conservation Status

The populations on either side of the Cascades are considered separate subspecies and have a number of differences. Breeding Bird Survey records have shown a significant population increase throughout Washington from 1966 to 1991. Christmas Bird Count numbers have also been increasing recently, which may be the result of more complete coverage in Marsh Wren habitat rather than an actual increase of wintering birds. While Marsh Wrens readily colonize created wetlands and nest in invasive plants such as purple loosestrife, wetland loss and degradation are a concern for this species.

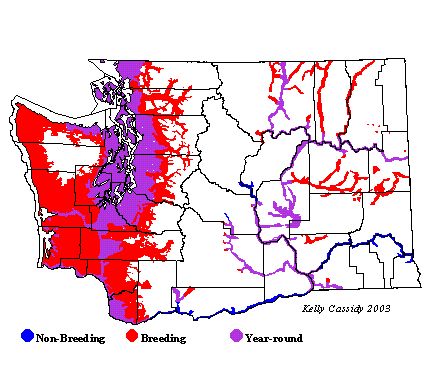

When and Where to Find in Washington

Marsh Wrens are abundant where there is appropriate habitat. During the breeding season, they are found throughout western Washington and in Grant and Adams Counties, the Yakima Valley, Grand Coulee, and along the Columbia River. In winter, they are still common in western Washington, even in small marshes. Most eastern Washington Marsh Wrens leave by mid-October and return in March, but some stay through the winter at lower elevation.

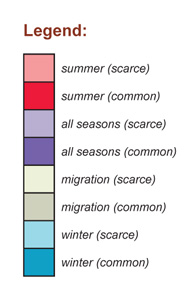

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | F | F | F | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | F | F |

| Puget Trough | F | F | F | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | F | F |

| North Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | |||||

| West Cascades | R | R | R | U | U | U | U | U | U | R | R | R |

| East Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | ||||

| Okanogan | U | U | U | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | U | U |

| Canadian Rockies | F | F | F | F | U | |||||||

| Blue Mountains | R | R | U | U | U | U | U | |||||

| Columbia Plateau | U | U | F | C | C | C | C | C | F | U | U | U |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map